Energy transition now as a weapon against Russia: Democratic inertia versus decisiveness

Sjeng Scheijen (NRC 15/2/25 Vrede met Rusland bereikt Europa niet met meer wapens) stelt, dat Europa geen extra bewapening nodig heeft om Rusland te verzwakken, maar versneld moet inzetten op energietransitie om de Russische, op fossiele inkomsten gebaseerde economie te ondermijnen. Los van de klimaatcrisis, die de transitie onvermijdelijk maakt, zou een versnelling ervan Rusland strategisch verzwakken. Dit klinkt logisch, maar vereist enorme investeringen en offers in publieke voorzieningen, zoals zorg en onderwijs. De vraag is of een democratie dit snel genoeg kan realiseren.

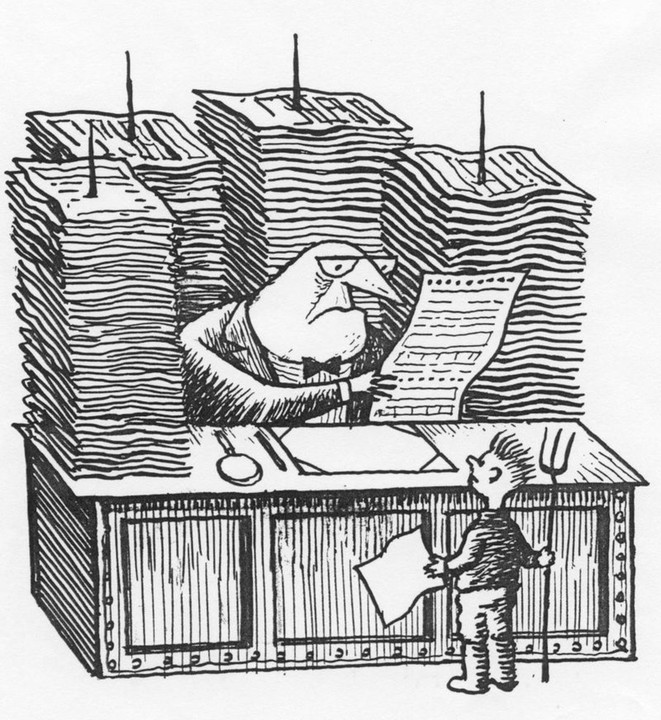

Europa’s besluitvorming is traag en verdeeld, terwijl Rusland en andere autocratieën met harde hand hun belangen doordrukken. Tegelijkertijd lijkt Amerika, onder invloed van Trump, zich terug te trekken uit de NAVO. Zijn isolationisme en Poetin’s expansionisme laten zien hoe geopolitiek wordt bepaald door sterke leiders.

Mijn kritiek op Scheijen is niet dat zijn strategie onhaalbaar is, maar dat hij de bestuurlijke realiteit negeert. Een versnelde energietransitie vereist een mate van centrale sturing die binnen democratische structuren moeilijk is. De paradox is wrang: om een autocratische dreiging te bestrijden, zou Europa tijdelijk autocratisch moeten handelen.

Als een versnelde energietransitie echt de sleutel is tot vrede, moet Europa beseffen dat democratische besluitvorming misschien niet snel genoeg werkt om deze omslag op tijd te maken.

Sjeng Scheijen (NRC 15/2/25 Peace with Russia will not reach Europe with more weapons) states that Europe does not need additional armaments to weaken Russia, but must accelerate its energy transition to undermine Russia’s fossil-based economy. Regardless of the climate crisis, which makes the transition inevitable, accelerating it would strategically weaken Russia. This sounds logical, but requires enormous investments and sacrifices in public services, such as healthcare and education. The question is whether a democracy can achieve this quickly enough.

Europe’s decision-making is slow and divided, while Russia and other autocracies are pushing hard for their interests. At the same time, under the influence of Trump, America appears to be withdrawing from NATO. His isolationism and Putin’s expansionism show how geopolitics is determined by strong leaders.

My criticism of Scheijen is not that his strategy is unfeasible, but that he ignores administrative reality. An accelerated energy transition requires a degree of central control that is difficult within democratic structures. The paradox is bitter: to combat an autocratic threat, Europe would have to act autocratically temporarily.

If an accelerated energy transition is really the key to peace, Europe must realize that democratic decision-making may not work fast enough to make this transition in time.

Ricky Turpijn