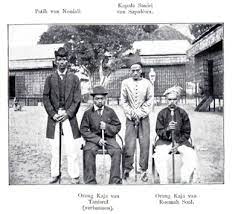

Taxation in the former Dutch East Indies. A game of haggling.

Alle Indische mensen hier in Nederland hebben een oermoeder afkomstig uit de inlandse bevolking in het Voormalig Nederlands-Indië, een ‘njai’. Grote kans, dat zij – geen cent te makken – belasting heeft betaald aan de Nederlandse koloniale macht. In de vorm van het verplicht planten van gewassen die naar Nederland geëxporteerd werden. Of door verplicht arbeid te verrichten aan deze gewassen. Belastingheffing was voor Nederland niet in de eerste plaats een instrument om geld te innen. Nederland wilde via de invoering van een belastingstelsel een koloniaal bestuur én beschaving naar Nederlandse maatstaven invoeren. Dat werkte toch anders uit volgens een promotie onderzoek van Maarten Manse, ‘Promise, Pretence and Pragmatism: Governance and Taxation in Colonial Indonesia, 1870-1940’. Lees de samenvatting op pg. 363.

All Indisch people here in the Netherlands have a primal mother from the native population in the Former Dutch East Indies, a ‘njai’. There is a good chance that she – not making a penny – paid taxes to the Dutch colonial power. In the form of compulsory planting of crops that were exported to the Netherlands. Or by doing compulsory labor on these crops. For the Netherlands, taxation was not primarily an instrument to collect money. The Netherlands wanted to introduce colonial administration and civilization according to Dutch standards by introducing a tax system. That worked out differently, according to a doctoral research by Maarten Manse, ‘Promise, Pretence and Pragmatism: Governance and Taxation in Colonial Indonesia, 1870-1940’. Read the summary on pg. 363.

Het beeld kantelt, dat gekoloniseerde mensen passieve buitenstaanders zijn. De systemen van sociale organisatie van de lokale bevolking waren cruciaal voor het kolonisatieproces. Belastingheffing werd een spel van afdingen tussen de belastingbetalers en dorpshoofden, aangewezen voor inning. En tussen dorpshoofden en belastingambtenaren. Fiscaal beleid werd pragmatisch van onderaf opgebouwd. Belastingheffing bood een arena voor het betwisten van de koloniale staat. Manse: ‘De wisselwerking tussen de koloniale machtshebbers en de bevolking en de tegenkracht die zij uitoefenden vond ik één van de interessantste conclusies van mijn onderzoek. En dat zie je mooi naar voren komen op zo’n klein belastingformulier.’ Volgens mij is toen ook de kiem gelegd voor de handelsgeest van de Indonesiër van nu, namelijk ‘tawar’, het afdingen. Als u zaken doet in Indonesië zult u dat zien. Op de ‘pasar’ en in de ‘boiling rooms’.

The image tilts, that colonized people are passive outsiders. The systems of social organization of the local population were crucial to the colonization process. Taxation became a game of haggling between the taxpayers and village chiefs, assigned for collection. And between village chiefs and tax officials. Fiscal policy was constructed pragmatically from the bottom up. Taxation provided an arena for challenging the colonial state. Manse: ‘I found the interaction between the colonial rulers and the population and the counterforce they exerted one of the most interesting conclusions of my research. And you can clearly see that on such a small tax form.’ I think that was also where the seed was sown for the commercial spirit of today’s Indonesians, namely ’tawar’, haggling. If you do business in Indonesia you will see that. On the ‘pasar’ and in the ‘boiling rooms’.

Ricky Turpijn